How Does Background Knowledge Impact Comprehension?

I’ve finally managed to get my hands on a copy of ‘Shifting the Balance’ (3-5) by Katie Egan Cunningham, Jan Burkins & Kari Yates and have been loving it so far!

It’s one of those professional books that just ‘makes sense’ and clearly articulates practical, research-based, science-aligned shifts that teachers can implement in the upper elementary literacy classroom.

One area that the authors explore in the first chapter, that has resonated deeply with me, is that of background knowledge.

While reading I found myself reflecting on many first-hand experiences where I’d witnessed the impact of background knowledge on students’ comprehension. I remember a time when the majority of my class struggled with an assessment passage about a blizzard; unsurprising considering we lived in the Middle Eastern desert and a blizzard was something most students have never even heard of, let alone experienced. I also remember feeling the need to skip certain leveled books used for running record assessments, knowing that many students simply didn’t know enough about the topic to truly show me their reading ability.

On the flip side, I’ve also seen students who often had difficulty with comprehension demonstrate exceptional understanding when reading a text about a topic they knew a lot about. These experiences often made me question, as I am sure you have too, the validity of text 'levels’ when it seems there are so many factors (such as background knowledge) that can impact a reader’s comprehension beyond his or her ability to decode the text.

Background knowledge, however, isn’t just about learning topic-related facts. It encompasses a wide range of lived experiences and prior knowledge that a reader brings to the table when engaging with a text.

“Children build prior knowledge through personal, educational and cultural experiences” (Cunningham, Burkins & Yates, 2023, p.17).

The authors of ‘Shifting the Balance’ identify five types of knowledge for comprehending: Cultural and Linguistic Knowledge, Strategic Knowledge, Textual Knowledge, Word Knowledge and Content Knowledge. These diverse forms of knowledge work together to provide learners with a foundation upon which new learning can occur.

And here’s the important thing. When we think about how we approach the teaching of reading in the upper elementary classroom, strategy instruction alone (e.g. inferring, identifying main idea, making connections etc.) is insufficient if students lack enough background knowledge to make sense of a text. Without these diverse forms of knowledge working in synergy when a learner encounters a new topic, deep comprehension of reading material about that topic will be challenging.

The authors demonstrate this point using photographs and the example of making inferences. I’ll use some different photographs to show this same idea.

Let’s have a look at this first photograph. So long as we have a little bit of background knowledge about riding a bike, we can pretty easily infer that a father is helping his child learn to ride a bike. It’s likely that the training wheels have just come off! This is an inference we can make based on the fact that he is holding the seat of the bike to keep it steady. We use clues in the picture, combined with our own knowledge and experiences, to make a fairly confident inference about what’s going on.

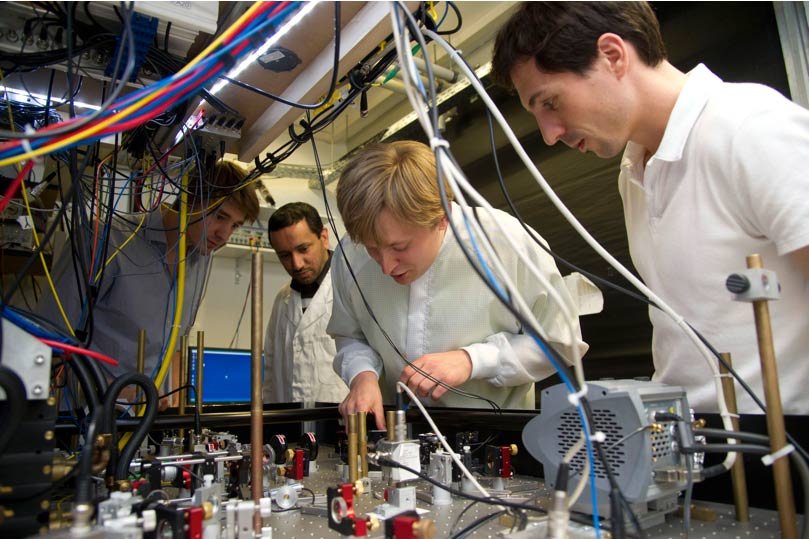

Now, let’s have a look at this second photograph. A little trickier to infer what’s going on, isn’t it? Unless, of course, you have some background knowledge in quantum physics!

Source: NBC News

In this photo, scientists are working on splitting an atom and putting it back together again. If you, like me, had some difficulty inferring exactly what was happening, it’s not because we need more practice making inferences! Common sense tells us that not having any knowledge about the equipment used to conduct such experiments greatly impacts our ability to infer what’s going on.

So, the question is, what does this mean for our instruction?

Having this understanding of the impact of background knowledge on comprehension is powerful! While we can’t control the prior knowledge and experiences that our students come into our classrooms with, we CAN intentionally plan for background knowledge building. Dedicating time to working out where our students may have gaps in background knowledge can help us to better prepare our readers for engaging with content-rich, worthwhile texts and target our instruction where it matters.

The bottom line is, extensive time spent teaching reading strategies such as identifying main idea, inferring, making connections and using context clues will be ineffective if a reader doesn’t have enough background knowledge to understand what a text is about.

So, next time you see comprehension breaking down for a student, try to establish whether he or she has enough background knowledge to make sense of the text. If they don’t, taking some time to intentionally and strategically fill in those gaps could be a powerful step toward helping that student engage more deeply and meaningfully with the topic. And that is a high leverage teaching move worth our time!